Linux/Umgebung/Variable: Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

| Zeile 1: | Zeile 1: | ||

'''topic''' - Kurzbeschreibung | |||

== Beschreibung == | |||

== Installation == | |||

== Syntax == | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang="bash" highlight="1" line> | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

=== Optionen === | |||

=== Parameter === | |||

=== Umgebungsvariablen === | |||

=== Exit-Status === | |||

== Anwendung == | |||

=== Fehlerbehebung === | |||

== Konfiguration == | |||

=== Dateien === | |||

<noinclude> | |||

== Anhang == | |||

=== Siehe auch === | |||

{{Special:PrefixIndex/{{BASEPAGENAME}}}} | |||

==== Dokumentation ==== | |||

===== RFC ===== | |||

{| class="wikitable sortable options" | |||

|- | |||

! RFC !! Titel | |||

|- | |||

| [https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/0000 0000] || | |||

|} | |||

===== Man-Pages ===== | |||

===== Info-Pages ===== | |||

==== Links ==== | |||

===== Projekt ===== | |||

===== Weblinks ===== | |||

= TMP = | = TMP = | ||

== General == | == General == | ||

| Zeile 129: | Zeile 163: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

CategorySystemAdministration | CategorySystemAdministration | ||

</noinclude> | |||

= Linux environment variables = | = Linux environment variables = | ||

Version vom 7. August 2024, 08:12 Uhr

topic - Kurzbeschreibung

Beschreibung

Installation

Syntax

Optionen

Parameter

Umgebungsvariablen

Exit-Status

Anwendung

Fehlerbehebung

Konfiguration

Dateien

Anhang

Siehe auch

Dokumentation

RFC

| RFC | Titel |

|---|---|

| 0000 |

Man-Pages

Info-Pages

Links

Projekt

Weblinks

TMP

General

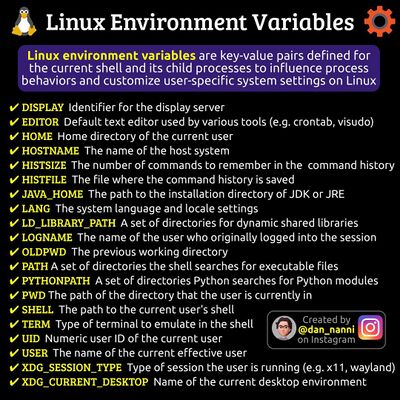

Environment variables (environ(7)) are named strings available to all applications. Variables are used to adapt each application's behavior to the environment it is running in. You might define paths for files, language options, and so on. You can see each application's manual to see what variables are used by that application.

That said, there are several standard variables in Linux environments:

* PATH = Colon separated list of directories to search for commands. * HOME = Current user's home directory. * LOGNAME = Current user's name. * SHELL = The user's preferred shell. * EDITOR = The user's preferred text editor. * MAIL = The user's electronic mail inbox location.

To see your currently defined variables, open up your terminal and type the `env` command.

Variables are defined with name-value pairs: `NAME=any string as value`. The variable name is usually in capital letters. Anything that follows the equal-sign is considered the variable's value until the terminating line feed character. Variables can be defined ad hoc in a terminal by writing the appropriate command. In Bash this would be `export MYVAL="Hello world"`. In this case the variable stays defined until the end of the terminal session.

If you want to append something to a variable, instead of overwriting the previous value, include the variable name into the new definition. E.g. in Bash: `export PATH=$PATH:~/bin`. This example shows how to append the bin directory in the user's home directory onto the PATH environment variable.

In most cases it is most convenient to store these variables in a configuration file that is read during system boot and user login so that they are available automatically. Unfortunately this not always as easy as it sounds. Why? For a couple of reasons:

1. Most programs don't read a configuration file to set their environment; instead, they inherit it from a parent process. You need to configure the parent's settings so that it passes them on for all its children. 1. Various shells and window managers are often the parent programs we are looking for, but each of them reads a different configuration file (dot file) when it starts. 1. Some Desktop Environments launch programs through an auxiliary service, and therefore the window manager may not be the parent program we're looking for.

So, with this knowledge we understand that we need to consider both the starting order of system processes and the configuration files they read when they are started. See the DotFiles page, or read on ...

Let's get to it! There are several ways you can access your Linux box: from a text console, from a graphical login (Display Manager), or using remote ssh.

Using text console or remote ssh

Text console logins and remote ssh logins both end up with a login shell. Variables are acquired in stages, by multiple processes in sequence. Each process adds some more variables.

1. At the end of boot the mother of all processes `init` is started. `init`'s environment, including PATH, is defined in its source code and cannot be changed at run time. 1. `init` runs the start-up scripts from `/lib/systemd/system` (under systemd) or `/etc/rc?.d` based on the run level set in `/etc/inittab` (under sysvinit). Each service or script defines its own required environment variables. Under systemd, variables defined in various `environment.d` directories will be made available to systemd user units; see the environment.d(5) manual page for details. 1. At the end of booting, `init` runs a `getty` process on one or more virtual consoles. `getty` waits for the user to type their name, after which it sets the `TERM` variable and executes `login` to prompt for a password. 1. `login` checks `/etc/passwd` and `/etc/shadow` for the user's account details. If the password is acceptable, `login` sets `HOME`, `SHELL`, `PATH`, `LOGNAME` and `MAIL` based on the contents of `/etc/passwd`, checks PAM, and finally runs the user's login shell. a. PAM may instruct `login` to read the variables in `/etc/environment` also. This is the default. 1. The login shell starts and reads its shell-specific configuration files. a. DebianPkg:bash first reads `/etc/profile` to get values that are defined for all users. After reading that file, it looks for `~/.bash_profile`, `~/.bash_login`, and `~/.profile`, in that order, and reads and executes commands from the first of these files that exists and is readable. See DotFiles for full details. a. (please fill in other shells as well)

For ssh logins, the chain is similar. The `init` system runs the `sshd` service, which listens for remote client connections.

1. `sshd` has a starting environment defined by its service file. 1. PAM may supply additional variables. 1. `/etc/ssh/sshd_config` defines additional environment variables that may be accepted from the client. 1. After authentication, sshd runs a login shell, which reads its shell-specific dot files as indicated above.

Now the environment variables are ready to be used by the applications you start from the shell.

Using graphical display manager

The login process is quite different under a DisplayManager.

1. At the end of booting, the mother of all processes -- `init` -- is started. 1. `init` runs services as described above. One of these services will be your display manager. 1. When the user successfully logs in, the display manager checks PAM, and then starts an Xsession. a. PAM may instruct the DM to read the variables from `/etc/environment`. 1. The Xsession reads `~/.xsessionrc` and possibly other files depending on the session type.

Whether shell's startup files (`/etc/profile` and `~/.profile` and so on) have an effect during graphical logins depends on the DisplayManager. For example SDDM loads them by default while they ignored by LightDM out of the box configuration in Debian. A user may choose to create a `~/.xsessionrc` file which reads these files.

Desktop Environments and systemd user services

Some Desktop Environments launch programs via systemd user services. These programs do not inherit their environment from the X session. To configure the environment for such programs, one must configure the `systemd --user` daemon.

This may be done as follows:

* `mkdir -p ~/.config/systemd/user/service.d`

* Use your preferred text editor to create a file inside this directory. The filename must end with `.conf` or it won't be recognized. Let's say you use `env.conf` as your filename. Inside the `env.conf` file, place the following lines:

. {{{

[Service] Environment="MYVAR=some value" }}}

* For a list of escape sequences that may be used in this file, see systemd.unit(5). * `systemctl --user daemon-reload` * In some Desktop Environments, you may also need to restart a launcher or menu service, or perhaps log out and back in.

You may supply more than one environment variable, and you may also configure umask or resource limits here (see Setting default umask for details). You may have multiple files, or one file with multiple entries, as you see fit.

environment.d(5) provides another way to accomplish this, but it's limited strictly to environment variables (no umask or resource limits), and uses a different syntax. It also does not support the Specifiers (%h, etc.) that systemd.unit(5) defines, but instead has a pseudo shell variable expansion syntax.

Quick guide

For the hasty who just need to get the system running, here is what you can do:

* Put all global environment variables, i.e. ones affecting all users, into /etc/environment

* Remember, this file is read by PAM, not by a shell. You cannot use shell expansions here. E.g. `MAIL=$HOME/Maildir/` will not work!

* There is no shell-agnostic and login-independent solution to the problem of how to configure the environment for all users, beyond the trivial cases that PAM can handle.

* Put all your transient shell settings (aliases, functions, shell options) in ~/.bashrc

* Put all your environment variables in ~/.profile

* Create or edit file ~/.bash_profile and include commands:

{{{

if [ -f ~/.profile ]; then

. ~/.profile

fi

}}}

* Create or edit file ~/.xsessionrc and include the same commands as above.

* If you use a Desktop Environment, create an `env.conf` file as shown in the previous section.

This is a quick and dirty approach! Not for the pedantic user.

Notes and exceptions

SysV, Systemd and init

According to GW at [PATH revisited: one PATH to "rule the [Debian World"]], `/sbin/init` is what gets executed by the kernel, regardless of what init system is installed.

{{{ $ ps -fp 1 UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD root 1 0 0 Oct07 ? 00:01:58 /sbin/init

$ ls -l /sbin/init lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 20 Sep 20 08:15 /sbin/init -> /lib/systemd/systemd* }}}

startx from terminal

If you start X Window (the GUI) from a text console, your environment variables are already defined by your login shell, as explained above. However, the window manager may read the same files again (see below). This is usually not a problem, but you may get unexpected results, such as PATH having all entries listed twice.

Shell cascading

If you start another shell within the login shell (yes it is possible), the second one is a non-login shell. It will not read named start-up files but searches non-login start-up script from user's home directory instead. With Bash it is called `~/.bashrc`. To avoid specifying same values in two places usually the login-shell start-up script `~/.bash_profile` includes the `~/.bashrc` at the end of its execution. To implement include following into your `~/.bash_profile`: {{{ if [ -f ~/.bashrc ]; then

. ~/.bashrc;

fi }}}

Terminal windows in X

If you start terminal / console window in graphical desktop environment it will be non-login terminal and it will read only the user's non-login start-up script. For Bash this is `~/.bashrc`.

Using su

The `su` command is used to become another user during a login session. It is commonly used to get root permissions temporarily from normal session. In Stretch and earlier releases, the `su` command resets your PATH environment value to one defined in `/etc/login.defs` by ENV_PATH and ENV_SUPATH variables. In Buster and later releases, `su` does not change your PATH variable by default (for details, see `/usr/share/doc/util-linux/NEWS.Debian.gz`). You may tell it to do so by creating the file `/etc/default/su` and putting the line `ALWAYS_SET_PATH yes` in it.

Please note that using Gnome helper `gksu` from Gnome panel by default uses `su` internally (i.e. you may "lose" your PATH if you do not configure it in login.defs in stretch).

. Does this mean gksu simply fails outright in buster due to the missing /sbin et al. in PATH?

CategorySystemAdministration

Linux environment variables

Linux environment variables are dynamic values that influence the behavior and configuration of running processes and applications, providing essential information such as system paths, user information, and localization settings