Network Address Translation

Network Address Translation (NAT) - Übersetzung von IP-Adressen

Beschreibung

- Netzwerkadressübersetzung

- Sammelbegriff für Änderungen von Adressen im IP-Header von IP-Paketen (Layer-3 des OSI-Modells)

- NAT (genauer SNAT) ermöglicht die gleichzeitige Verwendung einer öffentlichen Adresse durch mehrere Hosts

- Üblicherweise übernimmt der Router im Netzwerk die SNAT, der die Verbindung zum Internet herstellt

- Oft ist dieser Router das Default-Gateway eines Hosts

Vorteile

- NAT hilft die Verknappung der IPv4 Adressen zu entschleunigen

- Dies geschieht durch die Ersetzung mehrerer Adressen für mehrere Endsysteme durch eine einzige IP-Adresse

- IP-Adressen eines Netzes können vor einem anderen Netz verborgen werden

- Somit kann NAT zur Verbesserung der Privatsphäre eingesetzt werden

- Dieselben IP-Adressbereiche können von mehreren abgeschlossenen privaten Netzwerken verwendet werden

- Es kommt zu keinen Adresskollisionen, da nach außen nur die IP-Adresse des NAT-Routers sichtbar ist

Nachteile

- Ein Problem an NAT ist, dass die saubere Zuordnung „1 Host mit eindeutiger IP-Adresse“ nicht eingehalten wird

- Durch das Umschreiben von Protokollen

- Ein Problem an NAT ist, dass die sall-Headern, was einem Man-in-the-middle-Angriff (MITM-Angriff[1]) ähnelt, haben insbesondere ältere Protokolle und Kryptografiesverfahren auf Netzwerk- und Transportebene durch diesen Designbruch Probleme.

- Ebenso leiden Netzwerkdienste, die Out-of-Band-Signalisierung (Telekommunikationssignalisierung) und Rückkanäle einsetzen, etwa IP-Telefonie-Protokolle, unter Komplikationen durch NAT-Gateways.

- Das Ende-zu-Ende Prinzip (Direktverbindung) wird verletzt, indem der NAT-Router das IP-Paket bzw. TCP-Segment verändert, ohne dass er selbst der verschickende Host ist.

NAT-Typen

| Option | Beschreibung |

|---|---|

| Source-NAT | Adresse des verbindungsaufbauenden Computers (Quelle) umschreiben |

| Destination-NAT | Adresse des angesprochenen Computers (Ziel) umschreiben |

Source-NAT

- Anwendung aufgrund der Knappheit öffentlicher IPv4-Adressen

- Eine spezielle Form der SNAT wird auch Masquerading bzw. Masquerade

- Port and Address Translation (PAT) oder Network Address Port Translation (NAPT) genannt

- Wird vor allem bei Einwahlverbindungen [2] genutzt

- Beim Maskieren wird automatisch durch einen Algorithmus die Absender-Adresse des Pakets in die IP-Adresse des Interfaces geändert, auf dem das Paket den Router verlässt

- Beim SNAT muss die (neue) Quell-Adresse explizit angegeben werden

- In privaten oder möglichst preisgünstigen Netzinstallationen wird Source-NAT als eine Art Sicherheitsmerkmal und zur Trennung von internen und externen Netzen eingesetzt

- Durch das Maskieren der Quell-IP-Adresse können die internen Rechner nicht mehr von außen direkt angesprochen werden.

Destination-NAT

- Destination-NAT wird verwendet, um das Ziel eines IP-Pakets zu ändern

- Meist findet DNAT Verwendung beim Ändern der öffentlichen IP-Adresse eines Internet-Anschlusses in die private IP-Adresse eines Servers im privaten Subnetz

- Diese Methode ist als „Port-Forwarding“ in Verbindung mit UDP / TCP - Verbindungen bekannt

- DNAT kann daher auch dazu genutzt werden, um mehrere, unterschiedliche Serverdienste, die auf verschiedenen Computern betrieben werden, unter einer einzigen (öffentlichen) IP-Adresse anzubieten

- Abgrenzung von DNAT auch NAT-Traversal bzw. NAT-T

Kategorisierung

- RFC 3489, der das Protokoll STUN zur Traversierung von NAT-Gateways beschreibt, ordnet diese in vier verschiedene Klassen ein.

Diese prototypischen Grundszenarien bilden in modernen NAT-Systemen allerdings oft nur Anhaltspunkte zur Klassifizierung punktuellen Verhaltens der Gateways.

- Diese benutzen teilweise Mischformen der klassischen Ansätze zur Adressumsetzung.

- Oder sie wechseln dynamisch zwischen zwei oder mehreren Verhaltensmustern.

- RFC 3489 ist durch RFC 5389 ersetzt worden, der diese Kategorisierung nicht mehr versucht.

Full Cone NAT

- Im Full Cone NAT-Szenario setzt ein Gateway interne Adressen und Ports nach einem statischen Muster in eine externe Adresse und deren Ports um.

- Externe Hosts bauen über die externen Adressen des NAT-Gateways Verbindungen zu internen Hosts auf.

- Full Cone NAT ist auch unter der Bezeichnung EnS port forwarding bekannt.

Restricted Cone NAT

- Im Restricted Cone NAT-Szenario erlaubt das Gateway die Kontaktaufnahme eines externen mit einem internen Host.

- Dem Verbindungsversuch muss eine Kontaktaufnahme des internen Hosts mit dem externen Host vorausgehen.

- Es wird dabei der gleiche Zielport verwendet.

Port Restricted Cone NAT

- Im Port Restricted Cone NAT-Szenario erlaubt das Gateway die Kontaktaufnahme eines externen mit einem internen Host.

- Dem Verbindungsversuch muss eine Kontaktaufnahme des internen Hosts mit dem externen Host vorausgehen.

- Es wird dabei der gleiche Zielport und der gleiche Quellport verwendet.

Symmetric-NAT

- Im Symmetric-NAT-Szenario wird jede einzelne Verbindung mit einem unterschiedlichen Quellport ausgeführt.

- Die Beschränkungen sind wie bei Restricted Cone NAT-Szenario.

- Jeder Verbindung wird ein eigener Quellport zugewiesen.

- Eine Initiierung von Verbindungen durch externe Hosts nach Intern ist nicht möglich.

Funktionsweise

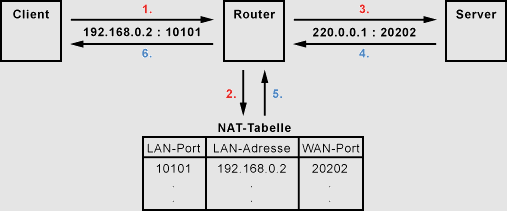

NAT-Router, NAT-Session und NAT-Table

- Ein moderner Router mit NAT-Funktion ist zustandsbehaftet (stateful).

- Beim stateful firewalling werden für jede seitens eines Clients angefragte Verbindung die zugehörigen Verbindungsinformationen (unter anderem IP-Adressen, Protokoll / Ports und Timeouts) in einer Session-Table gespeichert.

- Anhand der gespeicherten Informationen kann der NAT-Router dann das jeweilige Antwort-Datenpaket dem richtigen Client wieder zuordnen.

- Nach Ablauf einer Session wird ihr Eintrag aus der Session-Table gelöscht.

- Die Anzahl der Sessions, die ein NAT-Router gleichzeitig offen halten kann, ist durch seinen Arbeitsspeicher begrenzt.

- 10.000 Sessions belegen etwa 3 MB Speicherplatz

Source NAT (SNAT)

- Bei jedem Verbindungsaufbau durch einen internen Client wird die interne Quell-IP-Adresse durch die öffentliche IP-Adresse des Routers ersetzt.

- Ist der Ursprungsport belegt wird der Quellport des internen Clients durch einen freien Port des Routers ersetzt.

- Diese Zuordnung wird in der Session-Table (NAT-Table) des Routers gespeichert.

- Anhand der gespeicherten Informationen kann der NAT-Router dann das jeweilige Antwort-Datenpaket dem richtigen Client wieder zuordnen.

- Der Vorgang wird als Port Address Translation (PAT) bezeichnet.

| lokales Netz (Local Area Network/LAN) | öffentliches Netz (Wide Area Network/WAN) | |||

| Quelle | Ziel | Router ===== = =====> NAT |

Quelle | Ziel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 192.168.0.2:49701 | 170.0.0.1:80 | 205.0.0.2:49701 | 170.0.0.1:80 | |

| 192.168.0.3:50387 | 170.0.0.1:80 | 205.0.0.2:50387 | 170.0.0.1:80 | |

| 192.168.0.4:49152 | 170.0.0.1:23 | 205.0.0.2:49152 | 170.0.0.1:23 | |

- Beispiel Source-NAT und IP-Routing

- In diesem Beispiel nutzt das private Netz die IP-Adressen 192.168.0.0/24.

- Zwischen diesem Netz und dem öffentlichen Internet befindet sich ein Source-NAT-Router mit der öffentlichen Adresse 205.0.0.2/32.

- Ein Routing ist erforderlich, wenn Absender und Empfänger in verschiedenen Netzen liegen.

- Möchte eine über einen Source-NAT-Router angebundene Station ein Paket an einen Empfänger außerhalb seines (privaten) Netzes senden, so funktioniert der Kommunikationsprozess (vereinfacht dargestellt) wie folgt:

Ermittlungen

- Zuerst ermittelt die Station über DNS die Ziel-IP des Servers, und über die Routing-Tabelle den für das gewünschte Ziel nächstgelegenen Router, das sei hier der Source-NAT-Router.

- Dann ermittelt die Station per Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) dessen MAC-Adresse und baut ein Paket wie folgt zusammen:

- Es enthält

- Als Ziel-MAC-Adresse die MAC-Adresse des Source-NAT-Routers.

- Die Ziel-IP-Adresse des Empfängers (hier 170.0.0.1).

- Die Ziel-Portadresse für den Server.

- Die MAC- und IP-Adresse des Absenders (hier 192.168.0.4).

- Einen Absenderport (irgendeinen freien Port (high dynamic Port)) für die gerade anfragende Sitzung.

- Sowie andere (Nutz)Daten.

Empfang

- Der Source-NAT-Router empfängt und verarbeitet das Paket, weil es an seine MAC-Adresse gerichtet ist.

- Bei der Verarbeitung im Router wird das Paket in abgeänderter Form weitergeleitet.

- Der Router ermittelt anhand der Empfänger-IP-Adresse den nächsten Router.

- Er ermittelt per ARP dessen MAC-Adresse und baut das Paket wie folgt um:

- Es erhält nun abweichend die MAC-Adresse des nächsten Routers.

- Die Ziel-IP-Adresse des Empfängers (170.0.0.1), Ziel-Port

- Die öffentliche MAC- und IP-Adresse des Source-NAT-Routers (205.0.0.2), einen gerade freien Absender-Port aus dem Reservoir des Routers (hier 49152) und die Nutzdaten, die gleich bleiben.

Verarbeitung

- Durch NAT wird das Paket auf Schicht 3 wesentlich verändert

- Diese Zuordnung der ursprünglichen Absenderadresse und des Ports (192.168.0.4:49152) zum jetzt enthaltenen Adress-Tupel[3](205.0.0.2:49152) wird im Router solange gespeichert, bis die Sitzung abläuft oder beendet wird.

- Bei der Bearbeitung in nachfolgenden IP-Routern wird das Paket lediglich auf Schicht 2 verändert.

- Der Router ermittelt den nächsten Router, ermittelt per ARP dessen MAC-Adresse und baut das Paket wie folgt um:

- Es erhält nun abweichend als Ziel-MAC-Adresse die MAC-Adresse des nächsten Routers

- Die Absender-MAC-Adresse wird gegen die eigene ausgetauscht.

- Die IP-Adresse des Empfängers (170.0.0.1), Ziel-Port sowie die Absender-IP-Adresse des Source-NAT-Routers (205.0.0.2), dessen Absender-Port 49152 und die Nutzdaten bleiben erhalten.

- Das bedeutet: Auf Schicht 3 wird das Paket hier nicht verändert.

- Dieser Vorgang wiederholt sich, bis ein letzter Router die Zielstation in einem direkt angeschlossenen Netz findet.

- Dann setzt sich das Paket wie folgt zusammen:

- Es erhält als Absender-MAC-Adresse die des letzten Routers, als Ziel die MAC-Adresse der Zielstation, die IP-Adresse des Empfängers (170.0.0.1), Ziel-Port sowie die IP-Adresse des Absender-Source-NAT-Routers (205.0.0.2), dessen Absender-Port 49152 und natürlich Nutzdaten.

Abschluss

- Nach erfolgreicher Verarbeitung durch den Server wird die Antwort dann wie folgt zusammengestellt:

- MAC-Adresse des für den Rückweg zuständigen Routers (wobei Hin- und Rückroute nicht unbedingt identisch sein müssen).

- Die IP-Adresse des anfragenden Source-NAT-Routers (205.0.0.2), die Ziel-Portadresse 49152 sowie die MAC- und IP-Adresse des Servers (170.0.0.1) und dessen Absenderport , sowie Antwort-Daten (Payload).

- Nachdem alle Router durchlaufen wurden, wird daraus schließlich im Source-NAT-Router (205.0.0.2):

- MAC-Adresse und IP-Adresse des anfragenden Rechners (hier 192.168.0.4), und dessen Portadresse 49152 sowie die MAC des Source-NAT-Routers und IP-Adresse des Servers (170.0.0.1) und dessen Absenderport, sowie Antwort-Daten.

- Wird diese Sitzung beendet, wird auch Port 49152 wieder freigegeben.

Destination NAT (DNAT)

- Bei jedem Verbindungsaufbau durch den Client wird die Ziel-IP-Adresse durch die des eigentlichen Empfängers im LAN ersetzt.

- Außerdem wird der Zielport durch einen freien Port des Routers ersetzt, der dadurch belegt wird.

- Diese Zuordnung wird in der NAT-Table des Routers gespeichert.

| öffentliches Netz (WAN) | lokales Netz (LAN) | |||

| Quelle | Ziel | Router ===== = =====> NAT |

Quelle | Ziel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 170.0.0.1:1001 | 171.4.2.1:80 | 170.0.0.1:1001 | 192.168.0.2:80 | |

| 170.0.0.1:1001 | 171.4.2.1:22 | 170.0.0.1:1001 | 192.168.0.3:22 | |

| 170.0.0.1:1001 | 171.4.2.1:81 | 170.0.0.1:1001 | 192.168.0.3:81 | |

NAT-Traversal

- IPsec mit NAT-Traversal, oft nur als NAT-Traversal oder NAT-T bezeichnet, ist ein Verfahren zum Beheben von Problemen mit IPsec und Network Address Translation (NAT)[4].

- NAT-T findet Gebrauch bei IPsec-VPN, wenn IPsec (Encapsulating Security Payload) ESP-Pakete an Internet-Anschlüssen mit NATend Routern nutzt.

- Dabei werden die ESP-Pakete in UDP/4500 Pakete gepackt.

- Network Address Translation bricht das Gebot der Ende-zu-Ende-Konnektivität.

Techniken

- Keine universell anwendbaren Technik

- Anwendungen, die sich typischerweise von Host zu Host verbinden (z. B. bei Peer-to-Peer- und IP-Telefonie-Anwendungen oder VPN-Verbindungen) benötigen NAT-Durchdringungstechniken.

- Viele Techniken benötigen die Hilfe eines für beide Parteien direkt öffentlich zugänglichen Servers.

- Manche Methoden nutzen einen solchen Server nur für den Verbindungsaufbau.

- Andere leiten allen Verkehr der Verbindung über diesen Hilfs-Server.

- Die meisten Methoden umgehen damit oft Unternehmens-Sicherheitsrichtlinien.

- Deswegen werden in Unternehmensnetzwerken Techniken bevorzugt, die sich ausdrücklich kooperativ mit NAT und Firewalls verhalten.

- Sie müssen administrative Eingriffe an der NAT-Übergabestelle erlauben.

Protokolle

- SOCKS, das älteste Protokoll zur NAT-Durchdringung, ist weit verbreitet, findet aber wenig Anwendung.

- Bei SOCKS baut der Client eine Verbindung zum SOCKS-Gateway auf (dieser ist meistens direkt mit dem Internet verbunden).

- Die Kommunikation wirkt für den Kommunikationspartner so, als würde sie direkt vom SOCKS-Gateway stammen.

- Bei Heimanwendungen wird Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) genutzt, was eine dynamische Konfiguration eines port-forwardings durch den Client selbst ermöglicht.

- Einige Router unterstützen auch ESP-pass-through[5].

- Dabei werden die ESP-Pakete direkt an das VPN-Gateway durchgereicht und auf NAT-T wird verzichtet.

- Ein weiteres Beispiel für ein NAT-Traversal-Protokoll ist STUN[6], das eine hohe Bedeutung bei VoIP hat.

Portweiterleitung

Portweiterleitung - Weiterleitung einer Verbindung, die über ein Rechnernetz auf einem bestimmten Port eingeht, zu einem anderen Computer

Eine Portweiterleitung (englisch port forwarding) ist die Weiterleitung einer Verbindung, die über ein Rechnernetz auf einem bestimmten Port eingeht, zu einem anderen Computer.

- Da der entsprechende Netzwerkdienst nicht von dem weiterleitenden Computer selbst geleistet wird, ist die Bezeichnung virtueller Server irreführend.

- Die eingehenden Datenpakete werden hierbei per Destination NAT und die ausgehenden Pakete per Source NAT maskiert

- die Ziel- und Quelladressen ersetzt

- um die Anfrage an den tatsächlichen Server und dessen Antwort an den ursprünglichen Client weiterzuleiten

- Für Server und Client entsteht so der Anschein, die eingehenden Pakete stammten von dem Computer, der die Portweiterleitung betreibt.

- Port Forwarding wird oft dazu benutzt, FTP, Web-Server oder andere Server-basierende Anwendungen hinter einem NAT-Gateway zu betreiben

Portweiterleitung durch Router

- Ein Router, der beispielsweise mit einem privaten lokalen Netz und dem Internet verbunden ist, wartet dabei an einem bestimmten Port auf Datenpakete.

- Wenn Pakete an diesem Port eintreffen, werden sie an einen bestimmten Computer und gegebenenfalls einen anderen Port im internen Netzwerk weitergeleitet.

- Alle Datenpakete von diesem Computer und Port werden, wenn sie zu einer eingehenden Verbindung gehören, per Network Address Translation (NAT) so verändert, dass es im externen Netz den Anschein hat, der Router würde die Pakete versenden.

Portweiterleitung wird es Rechnern innerhalb eines LAN – welche von einem externen Netz nicht direkt erreichbar sind – somit möglich, auch außerhalb dieses Netzes, insbesondere auch im Internet als Server zu fungieren, da diese somit über einen festgelegten Port (und mittels NAT) eindeutig ansprechbar gemacht werden.

- Für alle Rechner im externen Netz sieht es so aus, als ob der Router den Serverdienst anbietet.

- Dass dem nicht so ist, lässt sich anhand von Header-Zeilen oder Paketlaufzeitanalysen erkennen.

- Beispiel

Eine größere Firma besitzt ein lokales Netzwerk, wobei mehrere Server nach außen (Internet) per ADSL-Router unter einer IP-Adresse (z. B. 205.0.0.1) auftreten. Jetzt möchte ein Client aus dem externen Netz (Internet) einen Dienst (z. B. HTTP/TCP Port 80) auf einem Server der Firma nutzen.

- Er kann jedoch nur den ADSL-Router der Firma für den Dienst (HTTP/TCP Port 80) unter der ihm bekannten IP-Adresse (205.0.0.1) ansprechen.

- Der ADSL-Router der Firma leitet die Anfrage für den Dienst (HTTP/TCP Port 80) an den entsprechenden Server im lokalen Netzwerk weiter.

- Eine Portweiterleitung wird also benötigt, wenn keine Port Address Translation (PAT) möglich ist, da die erste Anfrage von außen (z. B. Internet) kommt und mehrere Server nur unter einer IP-Adresse von außen ansprechbar sind.

Verbesserung der Sicherheit

- Ein anderes Anwendungsbeispiel für eine Portweiterleitung ist die Sicherung eines Kanals für die Übertragung vertraulicher Daten.

- Dabei wird Port A auf Rechner 1 mit Port B auf Rechner 2 verknüpft durch eine im Hintergrund aufrechterhaltene Verbindung zwischen zwei anderen Ports der beiden Rechner.

- Dies bezeichnet man auch als Tunneling.

- So kann beispielsweise eine unsichere POP3-Verbindung (Nutzername und Passwort werden in der Regel im Klartext übertragen) durch den Transport in einem SSH-Kanal abgesichert werden

- Der Port 113 auf dem POP-Server wird per SSH an den Port 113 des lokalen Rechners des Anwenders weitergeleitet.

- Das lokale E-Mail-Programm kommuniziert nun mit dem lokalen Port (localhost:113) statt mit dem Port des Servers (pop.example.org:113).

- Der SSH-Kanal transportiert dabei die Daten verschlüsselt über die parallel bestehende SSH-Verbindung zwischen den zwei Adressen.

- Das Abgreifen des Passworts durch einen mithörenden Dritten wird dadurch nahezu unmöglich.

- Voraussetzung für einen SSH-Tunnel ist ein zumindest eingeschränkter SSH-Zugang auf dem Server (pop.example.org), was Privatanwendern üblicherweise nicht gestattet wird.

Port Triggering

- Beim Port Triggering werden sowohl die Ports festgelegt, über die die Daten des Programms nach außen gesendet werden, als auch über welche Ports die Antworten wieder eingehen.

- Port Triggering erweitert damit die Technik der einfachen Portweiterleitung.

- Wenn ein Rechner über eine Anwendung, deren Ports im Port Triggering festgelegt wurden, Daten ins Internet sendet, speichert der Router die IP-Adresse dieses Rechners und leitet die eingehenden Antwortpakete, entsprechend an diese IP-Adresse weiter (zurück).

- Die Weiterleitung erfolgt hierbei jeweils an die IP-Adresse, von welcher die Anforderung kam, ohne dass diese in der Konfiguration hinterlegt ist.

- Allerdings ist es auch mit dieser Technik nicht möglich, auf einem Port eingehende Verbindungen gleichzeitig an mehrere Rechner weiterzuleiten.

- Bei Port Forwarding ist der Port immer offen, auch wenn der Dienst nicht benutzt wird.

- Im Gegensatz dazu erlaubt Port Triggering den eingehenden Datenverkehr erst, nachdem ein Rechner aus dem lokalen Netz einen entsprechenden Request in Richtung Internet gesendet hat, und schließt den Port nach einer gewissen Zeitspanne der Inaktivität automatisch wieder.

- Hieraus ergeben sich zwei Vorteile:

- Erhöhte Sicherheit

- Die eingehenden Ports sind nicht dauerhaft geöffnet.

- Das Forwarding braucht nicht mehr konfiguriert zu werden: Es ist nicht mehr nötig, feste interne IP-Adressen für das Forwarding der Ports anzugeben, da diese IP-Adresse durch den ausgehenden Datenverkehr auf dem Trigger-Port ermittelt werden kann.

- Wird Port Triggering auf einen Port gelegt, auf dem VoIP betrieben wird, ist es möglich, dass der VoIP-Dienst nur noch erreichbar ist, wenn vorher ein ausgehender Anruf getätigt wurde.

- Sobald der Port wieder geschlossen wird (siehe oben) ist es wieder nicht möglich, eingehende Anrufe zu empfangen.

- Einige VoIP-Endgeräte unterstützen daher die Aufrechterhaltung der Weiterleitung durch den Versand von Pseudo-Datenpaketen.

Sicherheit

Siehe auch

Dokumentation

RFC

Man-Pages

Info-Pages

Links

Einzelnachweise

Projekt

Weblinks

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_Address_Translation

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=network+address+translation&title=Special:MediaSearch&go=Go&type=image

- http://www.hh.schule.de/ak/nt/einwahlv.htm

- https://de.ryte.com/wiki/Tupel

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Man-in-the-Middle-Angriff#

- https://www.ip-insider.de/was-ist-nat-traversal-nat-t-a-921138/

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/IPsec#Encapsulating_Security_Payload_(ESP)

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Session_Traversal_Utilities_for_NAT

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Netzwerkadressübersetzung

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portweiterleitung

- https://portforward.com/help/porttriggering.htm (englisch)

Testfragen

Testfrage 1

Testfrage 2

Testfrage 3

Testfrage 4

Testfrage 5

TMP

Network address translation (NAT) is a method of mapping an IP address space into another by modifying network address information in the IP header of packets while they are in transit across a traffic routing device. The technique was originally used to bypass the need to assign a new address to every host when a network was moved, or when the upstream Internet service provider was replaced, but could not route the network's address space. It has become a popular and essential tool in conserving global address space in the face of IPv4 address exhaustion. One Internet-routable IP address of a NAT gateway can be used for an entire private network.

As network address translation modifies the IP address information in packets, NAT implementations may vary in their specific behavior in various addressing cases and their effect on network traffic. The specifics of NAT behavior are not commonly documented by vendors of equipment containing NAT implementations.

Basic NAT

The simplest type of NAT provides a one-to-one translation of IP addresses. RFC 2663 refers to this type of NAT as basic NAT; it is also called a one-to-one NAT. In this type of NAT, only the IP addresses, IP header checksum, and any higher-level checksums that include the IP address are changed. Basic NAT can be used to interconnect two IP networks that have incompatible addressing.

One-to-many NAT

The majority of network address translators map multiple private hosts to one publicly exposed IP address. In a typical configuration, a local network uses one of the designated private IP address subnets (RFC 1918). A router in that network has a private address of that address space. The router is also connected to the Internet with a public address, typically assigned by an Internet service provider. As traffic passes from the local network to the Internet, the source address in each packet is translated on the fly from a private address to the public address. The router tracks basic data about each active connection (particularly the destination address and port). When a reply returns to the router, it uses the connection tracking data it stored during the outbound phase to determine the private address on the internal network to which to forward the reply.

All IP packets have a source IP address and a destination IP address. Typically packets passing from the private network to the public network will have their source address modified, while packets passing from the public network back to the private network will have their destination address modified. To avoid ambiguity in how replies are translated, further modifications to the packets are required. The vast bulk of Internet traffic uses Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) or User Datagram Protocol (UDP). For these protocols, the port numbers are changed so that the combination of IP address (within the IP header) and port number (within the Transport Layer header) on the returned packet can be unambiguously mapped to the corresponding private network destination. RFC 2663 uses the term network address and port translation (NAPT) for this type of NAT. Other names include port address translation (PAT), IP masquerading, NAT overload and many-to-one NAT. This is the most common type of NAT and has become synonymous with the term "NAT" in common usage.

This method enables communication through the router only when the conversation originates in the private network since the initial originating transmission is what establishes the required information in the translation tables. A web browser in the masqueraded network can, for example, browse a website outside, but a web browser outside cannot browse a website hosted within the masqueraded network. Protocols not based on TCP and UDP require other translation techniques.

One of the additional benefits of one-to-many NAT is that it is a practical solution to IPv4 address exhaustion. Even large networks can be connected to the Internet using a single public IP address.

Methods of translation

Network address and port translation may be implemented in several ways. Some applications that use IP address information may need to determine the external address of a network address translator. This is the address that its communication peers in the external network detect. Furthermore, it may be necessary to examine and categorize the type of mapping in use, for example when it is desired to set up a direct communication path between two clients both of which are behind separate NAT gateways.

For this purpose, RFC 3489 specified a protocol called Simple Traversal of UDP over NATs (STUN) in 2003. It classified NAT implementations as full-cone NAT, (address) restricted-cone NAT, port-restricted cone NAT or symmetric NAT, and proposed a methodology for testing a device accordingly. However, these procedures have since been deprecated from standards status, as the methods are inadequate to correctly assess many devices. RFC 5389 standardized new methods in 2008 and the acronym STUN now represents the new title of the specification: Session Traversal Utilities for NAT.

Many NAT implementations combine these types, so it is better to refer to specific individual NAT behavior instead of using the Cone/Symmetric terminology. RFC 4787 attempts to alleviate confusion by introducing standardized terminology for observed behaviors. For the first bullet in each row of the above table, the RFC would characterize Full-Cone, Restricted-Cone, and Port-Restricted Cone NATs as having an Endpoint-Independent Mapping, whereas it would characterize a Symmetric NAT as having an Address- and Port-Dependent Mapping. For the second bullet in each row of the above table, RFC 4787 would also label Full-Cone NAT as having an Endpoint-Independent Filtering, Restricted-Cone NAT as having an Address-Dependent Filtering, Port-Restricted Cone NAT as having an Address and Port-Dependent Filtering, and Symmetric NAT as having either an Address-Dependent Filtering or Address and Port-Dependent Filtering. Other classifications of NAT behavior mentioned in the RFC include whether they preserve ports, when and how mappings are refreshed, whether external mappings can be used by internal hosts (i.e., its hairpinning behavior), and the level of determinism NATs exhibit when applying all these rules. Specifically, most NATs combine symmetric NAT for outgoing connections with static port mapping, where incoming packets addressed to the external address and port are redirected to a specific internal address and port.

Type of NAT and NAT traversal, role of port preservation for TCP

The NAT traversal problem arises when peers behind different NATs try to communicate. One way to solve this problem is to use port forwarding. Another way is to use various NAT traversal techniques. The most popular technique for TCP NAT traversal is TCP hole punching.

TCP hole punching requires the NAT to follow the port preservation design for TCP. For a given outgoing TCP communication, the same port numbers are used on both sides of the NAT. NAT port preservation for outgoing TCP connections is crucial for TCP NAT traversal because, under TCP, one port can only be used for one communication at a time, so programs bind distinct TCP sockets to ephemeral ports for each TCP communication, rendering NAT port prediction impossible for TCP.

On the other hand, for UDP, NATs do not need port preservation. Indeed, multiple UDP communications (each with a distinct endpoint) can occur on the same source port, and applications usually reuse the same UDP socket to send packets to distinct hosts. This makes port prediction straightforward, as it is the same source port for each packet.

Furthermore, port preservation in NAT for TCP allows P2P protocols to offer less complexity and less latency because there is no need to use a third party (like STUN) to discover the NAT port since the application itself already knows the NAT port.

However, if two internal hosts attempt to communicate with the same external host using the same port number, the NAT may attempt to use a different external IP address for the second connection or may need to forgo port preservation and remap the port.

</ref>

Implementation

Establishing two-way communication

Every TCP and UDP packet contains a source port number and a destination port number. Each of those packets is encapsulated in an IP packet, whose IP header contains a source IP address and a destination IP address. The IP address/protocol/port number triple defines an association with a network socket.

For publicly accessible services such as web and mail servers the port number is important. For example, port 80 connects through a socket to the web server software and port 25 to a mail server's SMTP daemon. The IP address of a public server is also important, similar in global uniqueness to a postal address or telephone number. Both IP address and port number must be correctly known by all hosts wishing to successfully communicate.

Private IP addresses as described in RFC 1918 are usable only on private networks not directly connected to the internet. Ports are endpoints of communication unique to that host, so a connection through the NAT device is maintained by the combined mapping of port and IP address. A private address on the inside of the NAT is mapped to an external public address. Port address translation (PAT) resolves conflicts that arise when multiple hosts happen to use the same source port number to establish different external connections at the same time.

Telephone number extension analogy

A NAT device is similar to a phone system at an office that has one public telephone number and multiple extensions. Outbound phone calls made from the office all appear to come from the same telephone number. However, an incoming call that does not specify an extension cannot be automatically transferred to an individual inside the office. In this scenario, the office is a private LAN, the main phone number is the public IP address, and the individual extensions are unique port numbers.

Translation process

With NAT, all communications sent to external hosts actually contain the external IP address and port information of the NAT device instead of internal host IP addresses or port numbers. NAT only translates IP addresses and ports of its internal hosts, hiding the true endpoint of an internal host on a private network.

When a computer on the private (internal) network sends an IP packet to the external network, the NAT device replaces the internal source IP address in the packet header with the external IP address of the NAT device. PAT may then assign the connection a port number from a pool of available ports, inserting this port number in the source port field. The packet is then forwarded to the external network. The NAT device then makes an entry in a translation table containing the internal IP address, original source port, and the translated source port. Subsequent packets from the same internal source IP address and port number are translated to the same external source IP address and port number. The computer receiving a packet that has undergone NAT establishes a connection to the port and IP address specified in the altered packet, oblivious to the fact that the supplied address is being translated.

Upon receiving a packet from the external network, the NAT device searches the translation table based on the destination port in the packet header. If a match is found, the destination IP address and port number is replaced with the values found in the table and the packet is forwarded to the inside network. Otherwise, if the destination port number of the incoming packet is not found in the translation table, the packet is dropped or rejected because the PAT device doesn't know where to send it.

Visibility of operation

NAT operation is typically transparent to both the internal and external hosts. The NAT device may function as the default gateway for the internal host which is typically aware of the true IP address and TCP or UDP port of the external host. However, the external host is only aware of the public IP address for the NAT device and the particular port being used to communicate on behalf of a specific internal host.

Applications

- Routing

- Network address translation can be used to mitigate IP address overlap. Address overlap occurs when hosts in different networks with the same IP address space try to reach the same destination host. This is most often a misconfiguration and may result from the merger of two networks or subnets, especially when using RFC 1918 private network addressing. The destination host experiences traffic apparently arriving from the same network, and intermediate routers have no way to determine where reply traffic should be sent to. The solution is either renumbering to eliminate overlap or network address translation.

- Load balancing

- In client–server applications, load balancers forward client requests to a set of server computers to manage the workload of each server. Network address translation may be used to map a representative IP address of the server cluster to specific hosts that service the request.

Related techniques

IEEE Reverse Address and Port Translation (RAPT or RAT) allows a host whose real IP address changes from time to time to remain reachable as a server via a fixed home IP address. PAT attempts to preserve the original source port. If this source port is already used, PAT assigns the first available port number starting from the beginning of the appropriate port group 0–511, 512–1023, or 1024–65535. When there are no more ports available and there is more than one external IP address configured, PAT moves to the next IP address to try to allocate the original source port again. This process continues until it runs out of available ports and external IP addresses.

Mapping of Address and Port is a Cisco proposal that combines Address plus Port translation with tunneling of the IPv4 packets over an ISP provider's internal IPv6 network. In effect, it is an (almost) stateless alternative to carrier-grade NAT and DS-Lite that pushes the IPv4 address/port translation function (and the maintenance of NAT state) entirely into the existing customer premises equipment NAT implementation. Thus avoiding the NAT444 and statefulness problems of carrier-grade NAT, and also provides a transition mechanism for the deployment of native IPv6 at the same time with very little added complexity.

Issues and limitations

Hosts behind NAT-enabled routers do not have end-to-end connectivity and cannot participate in some internet protocols. Services that require the initiation of TCP connections from the outside network, or that use stateless protocols such as those using UDP, can be disrupted. Unless the NAT router makes a specific effort to support such protocols, incoming packets cannot reach their destination. Some protocols can accommodate one instance of NAT between participating hosts ("passive mode" FTP, for example), sometimes with the assistance of an application-level gateway (see ), but fail when both systems are separated from the internet by NAT. The use of NAT also complicates tunneling protocols such as IPsec because NAT modifies values in the headers which interfere with the integrity checks done by IPsec and other tunneling protocols.

End-to-end connectivity has been a core principle of the Internet, supported, for example, by the Internet Architecture Board. Current Internet architectural documents observe that NAT is a violation of the end-to-end principle, but that NAT does have a valid role in careful design.

An implementation that only tracks ports can be quickly depleted by internal applications that use multiple simultaneous connections such as an HTTP request for a web page with many embedded objects. This problem can be mitigated by tracking the destination IP address in addition to the port thus sharing a single local port with many remote hosts. This additional tracking increases implementation complexity and computing resources at the translation device.

Because the internal addresses are all disguised behind one publicly accessible address, it is impossible for external hosts to directly initiate a connection to a particular internal host. Applications such as VOIP, videoconferencing, and other peer-to-peer applications must use NAT traversal techniques to function.

Fragmentation and checksums

Pure NAT, operating on IP alone, may or may not correctly parse protocols with payloads containing information about IP, such as ICMP. This depends on whether the payload is interpreted by a host on the inside or outside of the translation. Basic protocols as TCP and UDP cannot function properly unless NAT takes action beyond the network layer.

IP packets have a checksum in each packet header, which provides error detection only for the header. IP datagrams may become fragmented and it is necessary for a NAT to reassemble these fragments to allow correct recalculation of higher-level checksums and correct tracking of which packets belong to which connection.

TCP and UDP, have a checksum that covers all the data they carry, as well as the TCP or UDP header, plus a pseudo-header that contains the source and destination IP addresses of the packet carrying the TCP or UDP header. For an originating NAT to pass TCP or UDP successfully, it must recompute the TCP or UDP header checksum based on the translated IP addresses, not the original ones, and put that checksum into the TCP or UDP header of the first packet of the fragmented set of packets.

Alternatively, the originating host may perform path MTU Discovery to determine the packet size that can be transmitted without fragmentation and then set the don't fragment (DF) bit in the appropriate packet header field. This is only a one-way solution, because the responding host can send packets of any size, which may be fragmented before reaching the NAT.

DNAT

Destination network address translation (DNAT) is a technique for transparently changing the destination IP address of a routed packet and performing the inverse function for any replies. Any router situated between two endpoints can perform this transformation of the packet.

DNAT is commonly used to publish a service located in a private network on a publicly accessible IP address. This use of DNAT is also called port forwarding, or DMZ when used on an entire server, which becomes exposed to the WAN, becoming analogous to an undefended military demilitarized zone (DMZ).

SNAT

The meaning of the term SNAT varies by vendor:

- source NAT is a common expansion and is the counterpart of destination NAT (DNAT). This is used to describe one-to-many NAT; NAT for outgoing connections to public services.

- stateful NAT is used by Cisco Systems

- static NAT is used by WatchGuard

- secure NAT is used by F5 Networks and by Microsoft (in regard to the ISA Server)

Secure network address translation (SNAT) is part of Microsoft's Internet Security and Acceleration Server and is an extension to the NAT driver built into Microsoft Windows Server. It provides connection tracking and filtering for the additional network connections needed for the FTP, ICMP, H.323, and PPTP protocols as well as the ability to configure a transparent HTTP proxy server.

Dynamic network address translation

Dynamic NAT, just like static NAT, is not common in smaller networks but is found within larger corporations with complex networks. Where static NAT provides a one-to-one internal to public static IP address mapping, dynamic NAT uses a group of public IP addresses.

NAT hairpinning

NAT hairpinning, also known as NAT loopback or NAT reflection,.

The following describes an example network:

- Public address: . This is the address of the WAN interface on the router.

- Internal address of router:

- Address of the server:

- Address of a local computer:

If a packet is sent to , then the host at that address receives the packet.

If no applicable DNAT rule is available, the router drops the packet. An ICMP Destination Unreachable reply may be sent. If any DNAT rules were present, address translation is still in effect; the router still rewrites the source IP address in the packet. The local computer (. When the server replies, the process is identical to an external sender. Thus, two-way communication is possible between hosts inside the LAN network via the public IP address.

NAT in IPv6

Network address translation is not commonly used in IPv6 because one of the design goals of IPv6 is to restore end-to-end network connectivity. The large addressing space of IPv6 obviates the need to conserve addresses and every device can be given a unique globally routable address. Use of unique local addresses in combination with network prefix translation can achieve results similar to NAT.

Applications affected by NAT

Some application layer protocols, such as File Transfer Protocol (FTP) and Session Initiation Protocol (SIP), send explicit network addresses within their application data. FTP in active mode, for example, uses separate connections for control traffic (commands) and for data traffic (file contents). When requesting a file transfer, the host making the request identifies the corresponding data connection by its network layer and transport layer addresses. If the host making the request lies behind a simple NAT firewall, the translation of the IP address or TCP port number makes the information received by the server invalid. SIP commonly controls voice over IP calls, and suffers the same problem. SIP and its accompanying Session Description Protocol may use multiple ports to set up a connection and transmit voice stream via Real-time Transport Protocol. IP addresses and port numbers are encoded in the payload data and must be known before the traversal of NATs. Without special techniques, such as STUN, NAT behavior is unpredictable and communications may fail. Application Layer Gateway (ALG) software or hardware may correct these problems. An ALG software module running on a NAT firewall device updates any payload data made invalid by address translation. ALGs need to understand the higher-layer protocol that they need to fix, and so each protocol with this problem requires a separate ALG. For example, on many Linux systems there are kernel modules called connection trackers that serve to implement ALGs. However, ALG cannot work if the protocol data is encrypted.

Another possible solution to this problem is to use NAT traversal techniques using protocols such as STUN or Interactive Connectivity Establishment (ICE), or proprietary approaches in a session border controller. NAT traversal is possible in both TCP- and UDP-based applications, but the UDP-based technique is simpler, more widely understood, and more compatible with legacy NATs. In either case, the high-level protocol must be designed with NAT traversal in mind, and it does not work reliably across symmetric NATs or other poorly behaved legacy NATs.

Other possibilities are Internet Gateway Device Protocol, NAT Port Mapping Protocol (NAT-PMP), or Port Control Protocol (PCP), but these require the NAT device to implement that protocol.

Most client–server protocols (FTP being the main exception), however, do not send layer 3 contact information and do not require any special treatment by NATs. In fact, avoiding NAT complications is practically a requirement when designing new higher-layer protocols today.

NATs can also cause problems where IPsec encryption is applied and in cases where multiple devices such as SIP phones are located behind a NAT. Phones that encrypt their signaling with IPsec encapsulate the port information within an encrypted packet, meaning that NA(P)T devices cannot access and translate the port. In these cases the NA(P)T devices revert to simple NAT operation. This means that all traffic returning to the NAT is mapped onto one client, causing service to more than one client "behind" the NAT to fail. There are a couple of solutions to this problem: one is to use TLS, which operates at level 4 in the OSI Reference Model and does not mask the port number; another is to encapsulate the IPsec within UDP – the latter being the solution chosen by TISPAN to achieve secure NAT traversal, or a NAT with "IPsec Passthru" support.

Interactive Connectivity Establishment is a NAT traversal technique that does not rely on ALG support.

The DNS protocol vulnerability announced by Dan Kaminsky on July 8, 2008 is indirectly affected by NAT port mapping. To avoid DNS cache poisoning, it is highly desirable not to translate UDP source port numbers of outgoing DNS requests from a DNS server behind a firewall that implements NAT. The recommended workaround for the DNS vulnerability is to make all caching DNS servers use randomized UDP source ports. If the NAT function de-randomizes the UDP source ports, the DNS server becomes vulnerable.

Examples of NAT software

- Internet Connection Sharing (ICS): NAT & DHCP implementation included with Windows desktop operating systems

- IPFilter: included with (Open)Solaris, FreeBSD and NetBSD, available for many other Unix-like operating systems

- ipfirewall (ipfw): FreeBSD-native packet filter

- Netfilter with iptables/nftables: the Linux packet filter

- NPF: NetBSD-native Packet Filter

- PF: OpenBSD-native Packet Filter

- Routing and Remote Access Service: routing implementation included with Windows Server operating systems

- WinGate: third-party routing implementation for Windows

See also

- Anything In Anything (AYIYA) – IPv6 over IPv4 UDP, thus working IPv6 tunneling over most NATs

- Internet Gateway Device Protocol (IGD) – UPnP NAT-traversal method

- Teredo tunneling – NAT traversal using IPv6

- Carrier-grade NAT – NAT behind NAT within ISP.